Source – Andrew Zaleski – CNBC.com

It was the last Monday of March, and the McLaren Formula 1 racing team needed a new rear car wing. Over the weekend, the team competed in the Australian Grand Prix, the opening race of the 2017 Formula 1 season. The next race, in China, was less than two weeks away, and McLaren’s engineers wanted a more aerodynamic wing fitted to the race car. Normally, manufacturing a new rear wing takes a month. But with additive manufacturing, the wing was ready in time for the Chinese Grand Prix the weekend of April 7.

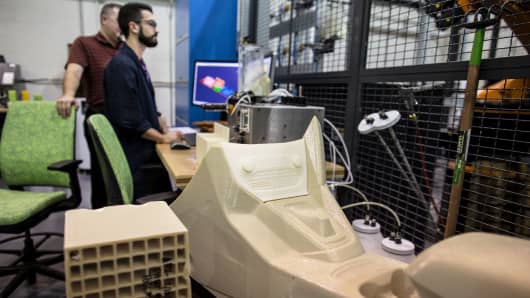

Additive manufacturing, more commonly known as 3-D printing, is the process by which heat and pressure fuse together thermoplastics or powdered materials to create a three-dimensional object. Unlike traditional manufacturing processes, which remove material to reach a finished product, additive manufacturing builds an object layer by layer over time.

It allows for more imaginative designs, more custom and creative products and, in already a few instances, cheaper manufacturing costs — and companies in several industries are taking notice. New Balance, Nike and Adidas have all incorporated 3-D printing into their companies to create mid-soles and spikes for athletic cleats. General Electric uses 3-D printing to create each of the 19 fuel nozzles that go into its new Leap jet engine.

“I have to believe that every automobile company has a serious eye toward it,” said Lonnie Love, head of the manufacturing systems research group at Tennessee-based Oak Ridge National Laboratory, the largest U.S. Department of Energy lab.

By 2020 the global market for 3-D printing technology is expected to reach $9.6 billion, according to Global Industry Analysts. A report from SmarTech Markets published last September said that the automotive market for 3-D printing is already worth $600 million.

Typically, the conversation around 3-D printing in the automotive industry centers on using it to develop prototypes of parts and new tooling methods rather than using 3-D printing itself to create parts that would be found in a completed car. Volkswagen and Ford, for instance, both use 3-D printing for prototyping to decrease design time. Ford, in fact, has been creating prototypes using 3-D printing for almost two decades.

Lately the conversation has begun to shift away from using 3-D printing solely for prototypes and toward using 3-D printing to produce parts that end up in automobiles.

During this year’s Formula 1 season, McLaren is using some 3-D-printed pieces in its MCL32 race car — a structural bracket for attaching a hydraulic line and a boot for coupling harness wires that make up the communications system the driver uses to talk to his pit crew.

“There’s no better test bed to have in the automotive world than Formula 1,” said Andy Middleton, president of the Europe, Middle East, and Africa headquarters of Stratasys, one of the world’s largest 3-D printing companies that is working with McLaren to produce parts. “If [3-D-printed parts] can live up to an environment like Formula 1, then we have great purpose to take them into motorsports and the automotive industry in general.”

Arizona-based Local Motors made a splash in 2014 when it revealed Strati, a drivable, 3-D-printed car built in a matter of days in partnership with ORNL; two years later, the company debuted Olli, a small 3-D-printed, self-driving passenger bus, in Washington, D.C.

But how soon 3-D-printed parts make their way into consumer cars is still difficult to say. At Ford, which recently launched an additive manufacturing research division in Dearborn, Michigan, there are still questions around the strength and durability of 3-D printed materials. Depending on the environment, the interior of a car can reach –40 degrees Fahrenheit in cold climates and hit 100 degrees Fahrenheit on hot summer days. Thermoplastics commonly used in 3-D printing cannot withstand those temperatures.

“It’s tough to have those plastics have the same performance regardless of temperature,” said Ellen Lee, the technical leader of additive manufacturing research at Ford. “We also have high requirements for humidity, ultraviolet exposure and odor, even.”

What’s more, the automotive industry is currently tailored to produce large quantities of cars at rapid speeds. Additive manufacturing is currently too slow and too unreliable to match the pace of an assembly line, which means it’s also too costly, at least for the auto industry.

There is, however, one killer application for 3-D printing in the automotive industry. Consider how McLaren was able to design a new race-car wing in under two weeks: A soluble mold was 3-D printed to create the shape of the wing, which was then wrapped in carbon fiber. Eventually the inside mold dissolved, leaving behind a structurally sound, carbon fiber wing. While the McLaren team didn’t use this new wing in the race, they proved to themselves that making a part as complex as a car wing could be done with speed and accuracy if needed.

It’s an example of tooling — making molds for one-of-a-kind parts found on cars. According to Oak Ridge National Laboratory’s Love, automotive companies will spend upward of $200 million per model of a car on tooling. So, for example, a car hood is made in a stamping process from a mold that usually takes six to nine months to mill out of a block of steel. Why not print the mold instead, something that will take a matter of weeks instead of months and at a much lower cost?

“One of the things we can never get back is time. If you look at car manufacturing, if it takes you two years to get your tooling manufactured, it’s going to take you at least four years to bring out a new car,” Love said. “But if you can get that lead time down from years to months, you can cut cycle times for new-car production in half.”

— By Andrew Zaleski, special to CNBC.com